Science & Education

Explore Our Articles

How The U.S Healthcare System Fails its Dementia Patients

The U.S. healthcare system is failing dementia patients through delayed diagnoses, lack of specialized care, and financial burdens. This article explores systemic gaps, the impact of stigma, and the urgent need for better training, early intervention, and policy changes to improve dementia care.

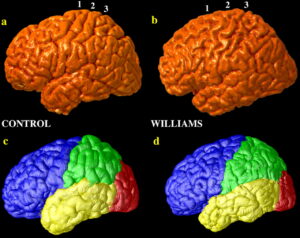

Understanding Williams Syndrome

Williams syndrome is a rare genetic disorder that affects brain structure, cognitive function, and physical health. Characterized by extreme sociability, distinct facial features, and cardiovascular issues, this condition offers a unique insight into the connection between genetics and behavior. Learn more about its causes, diagnosis, and the latest research shaping the future of Williams syndrome care.

Living With Williams Syndrome

Williams syndrome, often called the ‘Happy Syndrome,’ is a rare genetic condition that shapes both the joys and challenges of those who live with it. This article explores the social, emotional, and medical aspects of WS, highlighting the importance of support, advocacy, and inclusion for individuals and their families.

The Cycle of Housing Insecurity and Mental Illness in America

Discover how housing insecurity and severe mental illness create a relentless cycle in America. This article explores the impact of rising housing costs, eviction, homelessness, and inadequate mental health services—while highlighting solutions like integrated care and Housing First to break the cycle.

Living with Serious Mental Illness as an Adult

Living with serious mental illness (SMI) as an adult presents unique challenges, but with the right treatment, support, and understanding, recovery is possible. Learn about SMI, common misconceptions, and available treatments that help individuals lead fulfilling lives.

Alzheimer’s: Solving A Global Health and Economic Crisis

Alzheimer’s disease is a growing global health and economic crisis, affecting millions worldwide and placing immense strain on caregivers, healthcare systems, and economies. Advances in immunotherapy, AI-driven diagnostics, and biomarker research offer hope, but increased awareness, funding, and collaboration are crucial to combating this devastating disease.